As the world embraces a new year, there is a familiar sense of confidence in our digital progress. We speak fluently about artificial intelligence, automation, smart infrastructure, and autonomous systems. Technology feels mature, dependable, and ever-advancing. But is it?

Y2K38 Is a Mathematical Limit, Not a Software Bug

It’s early Tuesday morning on 19 January 2038, at 03:14:07 UTC. At this precise second, many computers around the world face a “digital rollover” known as the Year 2038 Problem (Y2K38). Some refer to it as the “new Y2K.” And while the potential for crisis is real, just as it was in 1999, the potential disasters are not what you think. CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

“The lesson of Y2K was not that the problem was exaggerated, but that early, serious attention prevented disaster.” — Uday Prasad

Just as mainframe-class systems played a critical role during the Y2K era, modern 64-bit enterprise platforms are structurally unaffected by the Y2K38 boundary. Rather, the Y2K38 problem is a digital countdown that runs out of space. It’s a fundamental mathematical limit hitting a specific storage size.

History has taught us that some of the most serious technology failures are not sudden; they are silent. They sit patiently inside systems we trust, waiting for a moment that feels far away, until it suddenly isn’t.

Y2K38 – Facts vs Fear

Most people remember the Y2K scare of 1999-2000 as a dramatic but ultimately harmless episode. Less understood is that Y2K did not mark the end of time-related computing failures. It merely marked the first chapter. The next chapter is far more complex, embedded, and difficult to reverse.

“Public awareness [about Y2K38] remains low, precisely because nothing appears to be broken yet.” — Uday Prasad

Y2K38 is rooted in how time has been represented in computing systems for decades. In countless operating systems, embedded devices, industrial controllers, and communication platforms, time is stored as a 32-bit signed integer counting seconds from a fixed point in 1970. This design choice, made when memory was expensive and system lifetimes were short, creates a hard mathematical limit.

On 19 January 2038, these systems will no longer be able to represent time accurately. When that limit is reached, time will overflow, wrap around, or behave unpredictably.

This is not speculation. It is not a bug that might happen. It is pure arithmetic.

The Dangers of Y2K38

What makes Y2K38 particularly dangerous is not just the failure itself, but where it lives. Unlike Y2K, which affected business applications and date fields that could often be patched or replaced, Y2K38 is embedded deeply within infrastructure. It affects

- Operating systems

- Firmware

- Embedded controllers

- Industrial equipment

None of these were designed to be replaced quickly or cheaply. Most of these systems are expected to operate for 20 to 30 years or longer. Plus, many are already deployed in ships, factories, power plants, ports, and transportation networks worldwide.

In these environments, upgrading software is not routine. It may require recertification, regulatory approval, operational downtime, and coordination with multiple vendors—some of whom no longer exist. In many cases, the affected systems are functioning as designed, and modifying them introduces more risk than leaving them unchanged.

“ In many cases, the affected systems are functioning as designed, and modifying them introduces more risk than leaving them unchanged.”

This reality is why Y2K38 remains largely unaddressed today. The problem is known, but the cost and complexity of fixing it locally are intimidating.

The Arithmetic of Y2K38

The problem of Y2K38 arises from computer systems that use a 32-bit signed integer to store a value known as Unix time.

In the early days of computing, specifically with the development of the Unix operating system in the late 1960s and early 1970s, developers needed a simple, consistent way to track time. They defined time as the ever-increasing count of seconds starting from a specific, arbitrary point: 00:00:00 Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) on Thursday, January 1, 1970. There are three major parts to understand how arithmetic matters for Y2K38.

1. Unix Epoch

The starting point of UTC is called the Unix Epoch. The logic was to choose a 32-bit signed integer to store this count (the time t variable). They used a signed integer so that negative numbers could represent dates before 1970 (e.g., 1969 or 1901) and positive numbers could represent dates after 1970.

The year 1970 was selected as a clean, logical starting point near the time of the Unix system’s creation. At the time, 68 years into the future, until 2038, seemed sufficient. (Consider that COBOL was only intended to last a few years as a stopgap language).

2. Bits and Integers

A bit is the smallest unit of digital data, representing either 0 or 1. A 32-bit system uses 32 of these 0s and 1s to represent a number. A signed integer is a way for a computer to store a whole number (such as 5, 100, or -50) that can be positive or negative.

When a number is “signed,” one of those 32 bits is reserved to indicate whether the number is positive or negative. This leaves 31 bits to store the actual positive value. Think of the first slot in a digital odometer. If the slot has a plus sign (+), the number is positive. If a number has a minus sign (-), it is negative.

In a computer’s binary memory, a 32-bit integer uses one of those 32 slots (bits) for the sign.

- If the first bit is 0, the number is Positive.

- If the first bit is 1, the number is Negative.

Because one bit is always reserved for the sign, only the remaining 31 bits are left to store the actual value or magnitude of the number.

The calculation of 2 raised to the power of 31 represents the total number of unique positive values you can count with 31 binary slots (bits).

The simplest way to understand this is to realize that 238 represents the total number of unique positive values you can count with 31 binary slots (bits).

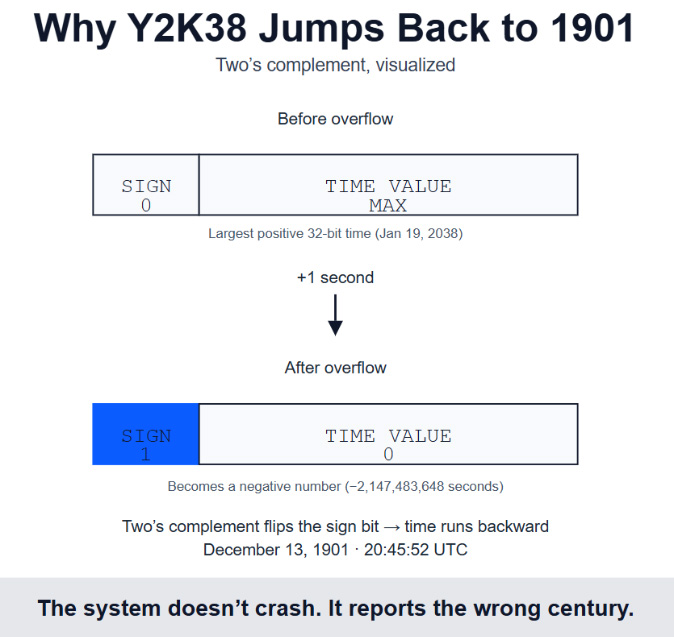

3. Two’s Complement

We know that T2K38 rollover returns to December 13, 1901, but why? This unusual date jump is due to the way computers handle negative numbers, known as two’s complement arithmetic. Two’s complement is a method for representing signed integers in binary, enabling straightforward arithmetic operations on both positive and negative numbers.

We know that the signed bit is in the leftmost position and is reserved to tell the computer whether the number is positive or negative. This bit is called the sign bit. When the sign bit is a 0, the number is positive. Because one bit is used for the sign, only the remaining 31 bits can be used to count the actual size (magnitude) of the number.

The maximum positive number is reached when:

The Sign Bit is 0 (meaning positive) and all remaining 31 bits are set to 1 (meaning the largest possible value).

Now add 1 second to it, and the number overflows:

- In a 32-bit register, this addition forces the leading bit to flip from 0 to 1, and all the other bits flip back to 0s. The number becomes 1000…000.

- Once this occurs, the number 1000…000 represents the most negative number, and counting backward 2,147,483,648 seconds from January 1, 1970, yields 20:45:52 UTC on Friday, December 13, 1901.

Today we are merely 12 years away from this boundary, and in industrial timelines, 12 years is not long. Major infrastructure decisions made today will still be in place in 2038. Systems being commissioned now may not be upgraded before the rollover occurs. And yet, public awareness remains low, precisely because nothing appears to be broken—yet.

It’s About Time Authority

What is often misunderstood is the nature of the problem itself. Y2K38 is not simply about broken clocks or incorrect dates. At its core, it is a question of where time authority resides.

As long as vulnerable systems are responsible for generating, interpreting, and storing authoritative timestamps, the risk persists. Attempting to teach every legacy device to understand a future for which it was not designed is neither practical nor scalable.

This shift in thinking opens the door to a more durable response to Y2K38. Rather than fighting the limitations of legacy systems, time authority itself can be relocated to environments explicitly designed for long-term operation, robust security, and 64-bit time representation. Enterprise-class platforms, including mainframes, have reliably handled such responsibilities for decades.

The important point is not the brand or the platform, but the architectural principle. When time authority is centralized, secured, and future-proofed, the rollover risk disappears. With it, stabilization is achieved without disrupting the operational systems on which the world depends every day.

Why Now — January 2026

Awareness must always precede action, and infrastructure does not change overnight. Rome wasn’t built in a day. Fleets do not modernize in a year. If Y2K38 is treated as a problem for “later,” it would arrive far sooner than expected.

The purpose of this reflection is not to alarm, but to remind. The lesson of Y2K was not that the problem was exaggerated, but that early, serious attention prevented disaster.

We still have time to act wisely. We still have time to prepare. We also have clarity that a safe, scalable path forward exists.

The most dangerous failures are those we assume will never happen—until the calendar proves otherwise.

Want more time-related content? Read Dr. Steve Guendert’s article, IBM z17 NTS Enhancements: Securing Time Synchronization.

Wouldn’t changing from signed arithmetic to unsigned arithmetic give us an additional 68 years?